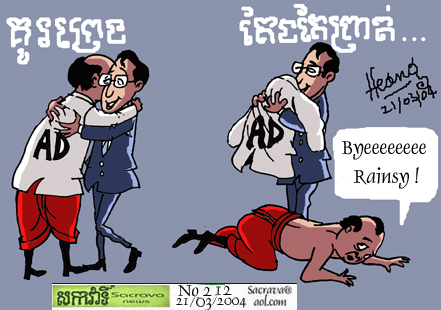

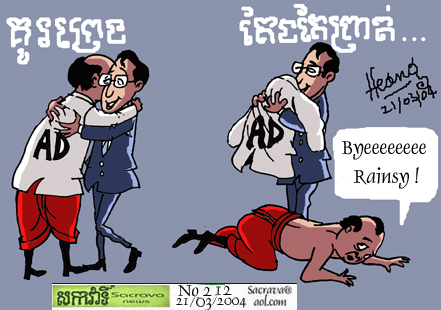

21 MARS 2004

ou

RAINSY

le baiseur

de

MIRAGES

!

| LES 6 COMMANDEMENTS |

COURRI@L 2004 | THE 6 COMMANDMENTS |

THOUSANDS OF

PHNOM PENH CHILDREN WORK FOR LITTLE OR NO WAGES

Radio Free

Asia : The International Labor Organization (ILO) revealed in

a recent survey that nearly 28,000

children work in household positions in Cambodia often for seven days

a week and for little or no wages, RFA reports. The survey found that

10 percent of children in Phnom Penh between the ages of seven and 17

work in such households. Duties include cooking, cleaning, washing, gardening,

or babysitting. Of the 27,950 children comprising this child labor force

in Phnom Penh, nearly 60 percent are girls. The ILO also found that 60

percent of the children work an entire day without rest and that 57 percent

of them are expected to work seven days a week. The ILO issued a statement

with the survey saying the use of children “for household work is becoming

increasingly common, due to a mixture of economic and social changes and

cultural factors.”

“I have

trouble helping these children who are forced to work at homes in Phnom

Penh because I rarely receive complaints from children or their families…”

Phnom Penh police chief Heng Peou told

RFA’s Khmer service. “We have no laws that allow police to enter a home

and investigate such matters when we have no evidence to go on. If we hear

complaints from the children’s mothers, we can help,” Heng Peou said.

About 80 percent of the child workers receive compensation in the form

of food, shelter, and education, and often work in relatives’ homes. However,

nearly 40 percent of child laborers who attend school

drop out and 14 percent remain illiterate. Several non-governmental

organizations (NGOs) in Cambodia, however, are taking steps toward helping

reduce the numbers of child laborers.

One NGO, the Cambodian Children

Against Starvation and Violence Association (CCASVA), receives financial

support from Save the Children Norway. The group is helping Phnom Penh’s

working children by paying them wages and allowing them to take breaks

for rest and food. “From our research, we see that many of the child

laborers come from families that suffer from domestic violence, gambling,

alcoholism, and divorce,” CCASVA executive director Phok Bunroeun told

RFA. Another NGO called the Cambodian Center for the Protection of Children’s

Rights (CCPCR) is working to draw more public attention to the plight of

child laborers. “Cambodian children are suffering too much from labor

exploitation and sexual trafficking…”

CCPCR executive director Yim Po told RFA. “[Child labor] is a big issue

we are trying to investigate. … There is no law to protect the children,

yet for the families who hire them, they need to respect the rules…” “CCPCR’s

problem is that once we receive information about a case of child labor

abuse, when we ask the child about the situation, he or she is afraid

to talk to us. We can only help if we get clear information…otherwise,

it’s very difficult,” Yim Po said. He said many children run the risk

of rape, beatings, or starvation when they work in other people’s homes.

Child labor in Cambodia has been

an ongoing problem. The U.S. State Department’s 2003 human rights report

found that “of children between the ages of 5 years and 17 years, 53

percent were employed…” with “the most serious child labor problems…in

the informal sector,” which includes domestic labor.

|

21 MARS 2004 ou RAINSY

|

The New

York Times Magazine : Traditionally, militant

groups huddle in caves in the mountains, or they blindfold journalists

and drive them in circles before depositing them at their leader's jungle

hideout. The Cambodian Freedom Fighters

(C.F.F.), a militant group dedicated to

the overthrow of Prime Minister Hun Sen of Cambodia, on the other

hand, meets each Saturday at 6 p.m. in an accountant's office in a strip

mall in Long Beach, Calif. When I called Yasith

Chhun, the group's leader, he didn't hesitate

to invite me to the next meeting. ''You can't miss our headquarters,''

he said. ''It's right next to the bridal shop.'' When I arrived, eight

people were seated in the office. The room was crammed not only with Cambodian

political paraphernalia but also with stacks of 1040 forms, evidence of

Chhun's double life as a tax preparer. One smiling C.F.F. devotee was offering

members glasses of fizzy orange soda. Chhun, 47, didn't cut a very imposing

figure. His stomach flopped over his slacks, and his bent legs, small head

and doughy face made him look more like a bowling pin than a warrior.

Still, a warrior

is decidedly what he is. The C.F.F.'s stated

goal is to enlist thousands of Cambodians to topple Hun Sen's quasi-authoritarian

government by force, creating chaos out of which, the group said, a better

government will emerge. ''Hun Sen -- believe

it or not -- he's going to get it,'' said one C.F.F. member, a muscular,

middle-aged man nearly spitting with rage. ''We are probably the last

hope for the 10 million Cambodians.'' Chhun said he has little idea

what form of government he plans to replace Hun Sen's with, though he has

two guiding principles: he wants to model a new regime as closely as possible

on the ideals of the American Republican Party, and he intends to

populate the government with lots of accountants.

Chhun passed around an attendance sheet so everyone could sign in. After

inking the sheet, each member stood up and pledged allegiance to the C.F.F.

Then the meeting began in earnest, with one member after another throwing

out ambitious, even wild chains of events that might put the group in control

of Cambodia. Chhun decided to expand the meeting by phone to include a

few members of the C.F.F.'s global network.

The group claims

to have hundreds of agents inside Cambodia ready to execute its violent

plans, each one known to C.F.F. members by a code of letters and numbers;

Chhun admits that the coding system is so complicated that he sometimes

loses track of which code represents which agent. He picked up the phone

and dialed, trying to reach one of his lieutenants in Southeast Asia. Unfortunately,

he had only 34 cents left on his international phone card and couldn't

dial out. Frustrated, he rummaged through desks and cabinets, found another

card and finally reached a C.F.F. agent in the field, a former Cambodian

Navy officer hiding along the Thai border. Speaking in Khmer, Cambodia's

language, the officer confidently reported that he had persuaded more than

400 government soldiers to turn against Hun Sen. (Chhun translated for

me as the rebel officer spoke.) ''All of them are ready,'' the officer

said. ''They're just waiting for my command.'' The speakerphone

crackled. ''They take an oath, they swear

to God they're with C.F.F. forever. They have the guns, they have the weapons,

they have tanks.''

It was impossible

to tell for sure whether the agent's report was genuine, exaggerated or

just wishful thinking. But it is clear that the C.F.F. isn't kidding around.

The group spent two years methodically planning a coup that culminated

in an armed assault on Phnom Penh in the fall of 2000, resulting

in some of the worst bloodshed in the Cambodian capital's recent history.

Now, Chhun said, the group is planning an even bigger assault. ''Next

time,'' he promised, ''we will attack the whole country.'' How does

a group get away with planning violent attacks overseas from an office

in Southern California? According to most Cambodia experts, the C.F.F.'s

actions are illegal, contrary to American policy and harmful to Hun Sen's

democratic opponents in Cambodia. Yet at least two conservative American

legislators who detest Hun Sen have advocated the removal, or even the

overthrow, of the Cambodian leader. That position, some believe, has had

the effect of helping provide political cover for the C.F.F. Now that the

White House

has embraced the idea of regime change in Iraq and other rogue nations,

the Cambodia hawks are getting a hearing, and the C.F.F. remains free to

plot in Long Beach.

Like any major

guerrilla attack, the C.F.F.'s November 2000 coup attempt was many years

in the making. After fleeing the Khmer Rouge as a teenager in the late

1970's, Chhun sought refuge in the United States in 1982. Like many Cambodians,

he maintained ties with his brutalized homeland, returning to assist an

opposition party in the early 1990's, when the United

Nations oversaw a transition to elected

governments. But Chhun grew incensed at repression by Hun Sen, a former

Khmer Rouge officer who used force and violent purges to remain in power

after losing the 1993 election. ''When I came back to the States,''

Chhun said, ''I felt that nonviolence cannot do anything to the dictatorship

in Cambodia.'' Chhun soon found a channel for his rage. In October

1998, Chhun and several other emigres held a clandestine meeting on the

Thai border with 120 Cambodian dissidents. Together they vowed to foment

a coup. Chhun returned to America and persuaded Cambodian-American friends

to join his nascent organization, the C.F.F. In May 2000, Chhun held a

fund-raiser attended by more than 500 people, many of them Cambodian expatriates,

on the Queen Mary, the old cruise ship permanently moored at Long Beach.

Attendees

raised their right hands and swore to overthrow the Cambodian government.

Chhun told them the money they were donating would be used to attack Hun

Sen. Through the fund-raisers, Chhun said, the C.F.F. amassed a war

chest of roughly $300,000. Money in hand,

Chhun and Richard Kiri Kim, a local Cambodian immigrant, recruited

20 or so Cambodian-Americans to travel with them to the Thai-Cambodian

border, where they set up a secret base. From there, Chhun dispatched Kim

into Cambodia to contact military officers and offer many of them money

and positions in a potential new government. In June 2000, Kim and his

colleagues brought several officers to the border to meet with Chhun, who

organized them into units and sent them back to recruit foot soldiers and

wait for a signal.

On Nov. 23,

2000, Chhun called Kim from the base on the border and told him to strike

the following day. Early on Nov. 24, a team of about 70 C.F.F. agents slipped

into the center of Phnom Penh. Armed with B-40 rockets and assault rifles,

they moved swiftly toward a compound of government buildings. They attacked

the Ministry of Defense and the Council of Ministers, peppering them with

fire, then turned their weapons on a local television station and a nearby

military base. State security forces engaged the group in a fierce firefight

that lasted more than an hour, leaving bullet holes in ministry offices

and blood pooled in the street. By daybreak, eight people lay dead. In

the wake of the violence, more than 200 people, including Richard Kiri

Kim, were arrested by the Cambodian police. Chhun fled to Thailand and

then returned to Long Beach to raise more money for the C.F.F., arriving

in time for the 2001 tax season. ''I couldn't keep my tax clients waiting,''

he said. Chhun defended his group by claiming he limits his actions in

the United States to raising money and planning strategy. But under the

Neutrality Act, it is illegal for American citizens on American soil to

organize military action against a country with which the United States

is not at war. And although Hun Sen has presided over political repression,

including using thugs to maim and kill critics, Washington has diplomatic

relations with the Cambodian government.

William Banks,

an expert on national security law at Syracuse University, explains that

the act prohibits even raising money or giving orders for violent attacks

from the United States. ''If you're providing the means -- money, weapons,

technology, intelligence -- from within the United States, you're violating

the law,'' Banks said. (...)

Yet so many

parties appear to benefit from Chhun that the United States government

probably won't be coming after him anytime soon. Unless, perhaps, the C.F.F.

unleashes more violence. In May, the group is holding another big fund-raiser

in Long Beach. And not long ago, I sat in Chhun's

office as he again made calls to his agents in Southeast Asia to discuss

a possible C.F.F. attack. He was particularly excited about the near future,

he said, when C.F.F. members will have more free time. ''Many of my

other leaders are in accounting,'' he said. ''I have to put off planning

attacks until after tax season.''

[ By JOSHUA KURLANTZICK ]

(Joshua

Kurlantzick is the foreign editor of The New Republic.)

| LES SIX COMMANDEMENTS |

REFORMING OUR BUDDHISM |

ROMAN POLITIQUE |

DIEU vs BOUDDHA |

GRAMMAR Introduction |

COURRI@L 2004 (Previous) |